Renewable Energy

Renewable EnergyLessons from the dim and distant past on how to reduce energy demand

Summary

Energy security is not a new issue. We had the oil crises of 1973 and 1979. It has been good this time round that there has been concerted action in the EU at least to reduce dependence on Russian gas. Improving energy efficiency has always been, and remains one of the most powerful, and potentially quickest action.

One of the really effective that has emerged is how much gas most homes are wasting, even the millions that have condensing boilers. At any one time, the cost-effective potential for reducing energy is probably 25-30% – and that has never changed, it is about ‘slack’ in the system.

Open full article

Lessons from the dim and distant past on how to reduce energy demand

The war in Ukraine, which now seems as if it will last a long-time, is one of the most important threats we face. Preventing, or in this case, correcting, the illegal annexation of a sovereign country by another country is fundamental and if Russia gets away with it, Europe and the world will be a more dangerous place. As everyone knows Russia can only act like this because of the huge inflows of money that result from selling gas to Europe. I wrote about energy security several times in 2013/14 – particularly when Russia invaded Crimea. I think back then Europe was sending Russia more than €0.5 billion a day (a day!) in return for oil and gas supplies. Just imagine a pile of a half a billion euros being carted off to Russia, (I know it is done electronically in reality).

Of course, energy security is not a new issue. We had the oil crises of 1973 and 1979 which highlighted dependence on oil from the Middle East. Trade is generally a good thing but by being energy dependent a country reduces it’s degrees of freedom of action. It has been good this time round that there has been concerted action in the EU at least to reduce dependence on Russian gas. Improving energy efficiency has always been, and remains one of the most powerful, and potentially quickest acting, levers that we have to reduce energy dependence. Obviously increasing domestic production of energy, of whatever source, is the other lever.

The EU through its RepowerEU initiative aims to bring down consumption by 15% by March 2023. For some reason the UK is almost alone is not responding to the war in Ukraine with a programme of at least encouraging, if not mandating energy saving despite the fact that in the UK 38% of gas is used for domestic heating and we are heading for a very hard winter that will see millions of people and businesses unable to pay their energy bill. Still, the government refuses to give any advice and only continues to issue anodyne press releases saying supplies are not threatened.

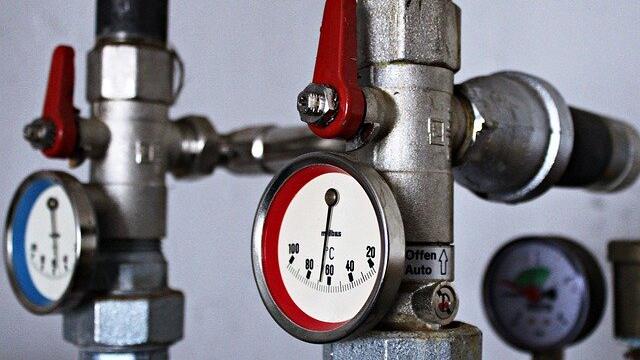

One of the really effective, and interesting things that has emerged is how much gas most homes are wasting, even the millions that have condensing boilers. When condensing boilers were introduced they were sold, and ultimately mandated, on energy saving grounds. Now it turns out – perhaps no surprise – that most of them have not been set up properly and are wasting 6-8%. This waste can be prevented by turning down the flow temperature, see here for details.

This conversation about boiler flow temps, which I’m glad to see is being turned into action, is a reminder that good energy management (for organisations or homes) consists of first managing what you have already got and then, and only then, considering investment opportunities, which can either be adding something to an existing system e.g. better controls on a heating system or lighting, or replacing something eg replacing a boiler with a heat pump, or conventional lighting with LEDs.

We learnt the basics of energy management in response to the oil crises of the 1970s (and before that the UK fuel crisis of the late 1940s) but somewhere along the line, as energy prices fell and incomes rose, they were largely forgotten. It is good to see them re-emerging, just disappointing that it takes another crisis.

The fact that homes with condensing boilers can save c.8% of gas consumption through simple re-adjustment of flow temperature shows two things:

1. The potential for cost-effective energy efficiency is still very large. At any one time, the cost-effective potential for reducing energy is probably 25-30% – and that has never changed, it is about ‘slack’ in the system. With higher prices the cost-effective potential increases. That 25-30% can usually be achieved with low cost measures and is before you get to the harder, more expensive stuff. I recently saw examples of schools saving 25%+ through low cost sensors that highlighted times of waste e.g. running heating when the building was closed or very early start times that were not justified by the weather.

2. The gas boiler industry has, with some notable exceptions, been woeful in its quality standards, training & integrity. What was the point of installing condensing boilers and claiming all the savings they were producing when they weren’t most of the time. Improving skill levels is essential, but is so improving basic integrity at senior levels within big organisations.

The idea that the government can’t or won’t do anything to give advice on energy saving is such nonsense, doing so would be an example of leadership, something that current politicians don’t seem to understand. Any information campaign does not have to be ‘authoritarian’ or ‘condescending’ – at the end of the day it is up to people whether they follow the advice but there is a real need for advice.

A case study. Back in the late 1980s I designed & ran an energy motivation programme for 45 of Coventry’s social services homes, mainly elderly people’s homes. These are some of the most difficult facilities to address in a way because: a) they are kept warm (usually too warm) all the time because residents are often sedentary and ‘need’ a high temperature – (or at least that was the belief structure) – and staff are non-technical, and they are rightly focused on their primary mission of administering care, often in difficult circumstances.

With the input from a wide range of stakeholders including the union we designed a motivation programme with a training course that:

1. explained WHY saving energy was important (which was all about budgets then, as it was pre conversations about carbon)

2. explained HOW to save energy, the usual simple tips

3. explained how to read meters (which is never easy) and record consumption (there were no smart meters back then).

Using the meter data we then gave them regular, simple weather corrected feedback (having explained how it worked), and the establishment received a percentage of the proven savings to spend on stuff that benefited the home. Often they spent it on additional simple energy saving measures, like draught proofing, adding a porch, etc., or on little niggly maintenance jobs that they had not succeeded in getting done through the system.

The net result was an overall 6% savings on energy use over a year, with individual savings ranging up to 38%. All of this was with no capital expenditure. The result was financial, energy, and carbon savings and engaged staff.

We developed a simple model which seems to work. In order to create Action, you need 2 things: Knowledge (or know-how) of what to do and the Motivation to do something. Training provides know-how and when done well can increase Motivation. Motivation is also (greatly) increased by Incentive, (which does not have to be financial), and Feedback that shows that the action is having the desired effect. Put those things together and you have effective action.

Other motivation campaigns at the time gave a percentage of savings to a charity chosen by the end-users, thus creating a double impact.

If we could do that with basically no technology, other than a spreadsheet, imagine what smart meters and cheap smart sensors can do. The schools saving 25% through smart sensors I referred to above are good examples.

We should be getting our energy management basics right before considering capital projects. Optimising energy consumption first can change what is viable or optimum for the capital projects, as well as reduce capital through techniques such as right-sizing. The differences between the 1980s and now are essentially: better technological options, increased motivation, and decarbonisation of electricity. When considering capital expenditure options the combination of climate change and the war in Ukraine should drive everyone to consider what would once have been considered radical, higher cost options including electrification and deep retrofits, rather than small improvements. At today’s prices many of these measures will be economic, the problem then is how to finance them, particularly in the residential sector. When assessing financial benefits we should also never forget, although most people do, the impact of energy price volatility, which in itself has a financial impact, irrespective of the energy price being made.

We know what to do to reduce dependence on dictators selling fossil fuels, along with all the other negative environmental, economic, and social impacts from their use. Let’s just do it.

The Coventry project is described here.